- Home

- Kate London

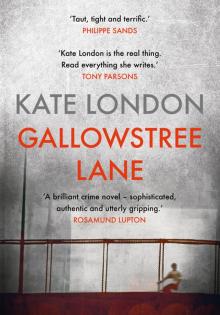

Gallowstree Lane

Gallowstree Lane Read online

GALLOWSTREE

LANE

Also by Kate London

Post Mortem

Death Message

GALLOWSTREE

LANE

KATE LONDON

First published in hardback in Great Britain in 2019 by Corvus,

an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Kate London, 2019

The moral right of Kate London to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978 1 78649 795 6

Trade paperback ISBN: 978 1 78649 338 5

E-book ISBN: 978 1 78649 339 2

Printed in Great Britain

Corvus

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.corvus-books.co.uk

For D & Y

Author’s Note

Special thanks to Sheldon and Michelle Thomas from the charity Gangsline, who shared their experience, understanding and passion so generously.

AFTERWARDS

FRIDAY 4 NOVEMBER 2016

Detective Inspector Sarah Collins had set off before dawn, whipping round London’s arterial roads, thundering along the motorway and then winding down country lanes to the Saxon church that lay, through a gate and along a path, on the brow of a small hill. The hedgerows and trees were flaming with late colour.

More than thirty minutes remained before the funeral. She slid the car seat back and drank her flask of tea. Caroline had offered to come with her, but it felt wrong to be so intimately together so soon after they had separated. She sighed and pressed the heels of her hands against her eyes. The only sound now was birdsong.

When she was only sixteen, Sarah’s sister had died. Susie’s boyfriend, Patrick, had been driving too fast and lost control on a sharp bend. It was no more than a moment’s misjudgement, a youthful thrill at the power of the car he had borrowed for the day, but in an instant her sister was as dead as if Patrick had taken a knife and killed her.

Sarah sighed again. It was tiresome to think of this so many years later and at such a very different funeral. But you can’t control what comes into your mind. Perhaps it was Susie’s youth when she died, or perhaps it was the vast sadness that Sarah felt now, expanding inside her like air.

The body is not a fairy tale. Sometimes it does not survive an impact or a stab wound or the bullet from a gun.

She wiped her eyes with the back of her hand and tidied her flask away. Into her mind had stepped the children who would follow the hearse today. There was no remedy for the loss of a parent: that was the thing she could not handle. When she was at work, Sarah could do her best to deliver justice, but today what could she contribute? She would sit alone at the back of the church. Pay her respects. Bother no one.

Other cars had started to arrive. They bounced up the bank and parked and spilled their occupants onto the verges. The funeral today was for a police officer, and so many of the mourners were also police. They were easy to recognize from their best-behaviour attitude and their smart clothes and the assessing way they met your eye.

There were children too, populating the graveyard as they spread out on their way to the church. Sarah smiled as she watched them. A chubby boy of about four in matching blazer and trousers. A slightly older girl in an apricot taffeta dress and dark cardigan – dressed more for a wedding than a funeral. Teenage girls in tight dresses and spike heels that sank into the path or wobbled beneath them. And teenage boys with gelled hair and outsized Adam’s apples, squeezed into horrible suits in tribute to the baffling adult world that couldn’t today be gainsaid.

Sarah’s heart went out to them in their poorly concealed vulnerability, their sensitivity to any slight, their hastily made mistakes and their painful, long-drawn-out regrets. As she watched the adults gathering in their offspring with varying degrees of patience, she knew that for all the push and pull of parenthood, these children were the lucky ones. Mum and Dad cajoling them towards their emergence from this desperate and grandiose and ridiculous time when even a haircut felt like a life-or-death event.

And as she left the car and walked through the gate towards the church, her thoughts travelled to those other teenage boys, on their bikes, stealing phones and slipping drugs hand to hand on the streets of London. Into her mind came Peter Pan’s lost boys roaming free, and Neverland, where to die was an awfully big adventure and where pirate Smee wiped his glasses before he cleaned his sword, and her gaze turned to the far edge of the churchyard, where, by a fence that separated the consecrated ground from a field of horses, the deep grave waited.

A PROMISING

FOOTBALLER

SUNDAY 9 OCTOBER 2016

1

Please don’t let me die.

The first time, Owen wasn’t sure he’d heard the words correctly. And he couldn’t see properly either. The street light wasn’t working. The big old park that ran alongside the pavement was pitch dark, and his eyes were still filled with the brightness of the shop where he had just been. At first, the only thing visible was a shifting in the shadows. Then, as his irises expanded, he made out two teenage boys standing with their backs against the railings.

Gallowstree Lane was too wide, too dark, and life had taught Owen the hard way never to take anything at face value. Perhaps these boys were going to rob him. But the boy who had spoken stepped forward, and Owen saw he was gripping the inside of his leg. A dark, sticky lake was spreading around his feet, and he said it again.

‘Please don’t let me die.’

Owen had only popped out to buy some fags from the corner shop before it closed. He had a boy of his own at home, a boy he had only ten minutes ago told to switch the lights out but who was probably still wide awake glued to his Xbox. He’d flick the lights off at his father’s return and pretend to be asleep. It always made Owen smile, and thinking of it stopped his breath for a second, because although his boy was all the things you’d expect of a teenager – lazy, messy, disorganized – Owen loved him so hard he knew he’d die for him.

The boy in front of him was, he guessed, about the same age as his own son. Fifteen. He tried not to let the thought of that paralyse him or make him leap to the outcome that the growing pool of blood suggested. He’d been trained not to give up, not just by the army, but by life too. He’d seen stuff. A soldier stepping on an IED. A suicide attack on a market. He was right back there and the familiar reaction – a certain cold sweatiness – was counteracted by the equally familiar instruction to himself. Do what you can. Don’t stop to think about outcomes.

He called out to the other boy, the one who seemed unharmed, and he stepped forward. Unremarkable: a London kid with the usual uniform of dark hoody and dark tracksuit trousers.

Owen said, ‘Have you called an ambulance?’

The boy shook his head. ‘Haven’t got a phone.’

‘You haven’t got a phone?’ Even in this moment of peril, Owen disbelieved. Surely every teenager had a phone?

He glanced at the boy again. His eyes were becoming accustomed to the thin light and he took in a bit more detail. Pale skin for a black lad, wide mouth, a line shaved in his left eyebrow. Superdry logo across the front of his hoody. The boy was probably shocked. In these situations you had to take charge, give clear instructions. He reached his own phone – an iPhone 6 – out of his pocket and handed it over.

‘My code’s 634655. Call 999.’

The boy fumbled anxiously with the phone. ‘Fucking hell! There’s no signal.’

‘Find a signal. Tell them there’s an off-duty paramedic on scene. The patient’s conscious and breathing but there’s a suspected arterial bleed. Have you got that?’

‘Suspected arterial bleed, yes.’

‘Tell them we need HEMS. You got that? HEMS. It’s the air ambulance.’

‘HEMS, yes.’

‘Tell them it’s life-threatening.’

The boy was still fumbling with the phone. ‘Fucking hell,’ he said again.

‘What’s your name?’

The boy shook his head – whether at the phone or refusing his name, it wasn’t clear.

‘OK. Whatever your name is, stop panicking. Find a signal. Make the call, then come back and help.’

He turned back to the wounded boy and said, ‘You need to lie down.’ But the boy was confused. He had started to take off his clothes, and as Owen approached, he tried to push him away.

He looked around and said it again, this time with rage and fear.

‘Don’t let me die.’

Two other people were passing. Young white kids, a boy and a girl. About twenty, maybe. Their steps faltered.

The boy said, ‘Is there a problem?’ He had one of those good-schools accents: out of place on this street. There was fear in his voice, and his eyes flickered to the pool of blood.

Owen was catching the victim as he began to lose control of his body, lying him down on the street even as he resisted like a fluttering bird. Looking up, he said to the kids, ‘This fella’s in trouble. Can you help me?’

‘What can we do?’

‘Put pressure on his leg.’

The boy knelt, put his two hands on the leg, pressing his thumbs. Owen said, ‘No. Much more force. Stand up. Put your foot in his groin, here. That’s right, use your weight. Don’t be afraid.’

He gestured to the girl. ‘You, darling. What’s your name?’

‘Fiona.’

Her skin was white as birch in the dark street, her eyes wide. She had long straight hair. He smiled and tried to sound encouraging.

‘Right, Fiona. Kneel down and rest his foot on your shoulder. Lift the leg. That’s right. Get it high up. We’re trying to slow the bleed.’

He knelt by the patient. ‘My name’s Owen, fella. What’s yours?’

The boy just groaned. Owen started searching for other wounds. The skin was already clammy. With the darkness and the blood it was hard to see the necessary detail. He didn’t have a torch, no dressings, no defib. Nothing.

He said, ‘What happened? Have you been stabbed more than once?’

‘Don’t know.’

Another woman had joined them. A fat black woman, fifties maybe. She had a steadiness about her and the light gleamed off her skin as if she was highly polished stone.

She said, ‘What can I do?’

The clothes the boy had taken off were on the pavement, and Owen gestured towards them. ‘Look through those. See if you can see other cuts.’

Studiously she began, holding the clothes up to catch what light there was.

The girl was wearing a scarf, and Owen asked her to give it to him. She surrendered it immediately. It might well be pointless but what else could he do? He wrapped the scarf tightly round the top of the thigh. The boy was losing consciousness. He had no blood to give him, no oxygen. He put his face towards the boy’s mouth. There was still breath. There was still hope. The police were here, already pulling on their plastic gloves, asking what they could do. Owen turned and looked over his shoulder. There was no sign of the boy he had told to call for help.

2

At first Ryan had been in a daze. He had stood for an aching while, watching the guy working on his friend. He was a black guy, buzz cut, jeans. Other people had gathered and the guy had shouted instructions. He seemed to know what he was doing. Everything would be OK. After all, lots of people do fine after they’ve been cut. That was true. That was true! He’d seen it.

Good scars they were: shown like trophies. A trouser leg pulled up: a patch where the knife had entered and the hair on the leg gone forever. Jeans pulled down: an ivory cord drawn tight and hard through the soft, warm skin of a thigh or a buttock. A shirt unbuttoned: silver lines like staples across a toughened line of tissue. These were the good scars: neat, professional. But sometimes too – because the medics always go to the cops – no criss-crosses. So instead a raised angrier band where a friend has helped and traced a streak of superglue along the line of the cut. What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger. That’s what everyone says, isn’t it?

Ryan had been lost in his hopes, but the focus of his gaze had returned to his friend, Spencer, lying floppy on the street. For a bit he had struggled, almost resisted the guy who was trying to help him, but then he had seemed to stop caring. He’d begun to wander around; the guy had held him. Then he’d lain down. There was a lot of blood. That was worrying. But they had all kinds of shit nowadays that could save a life. Loads of people get stabbed. Ryan had known he should leave, but Spence was his friend. He couldn’t remember a time when he hadn’t been his mate. He just couldn’t make his legs turn and carry him away.

Some of the blood had been seeping into a storm drain. Ryan had watched that for a while, his friend’s blood spilling into London’s sewer system, making its way through those dirty tunnels towards the river. He felt his own blood as if it was pooling into his feet. His face rigid, his bottom jaw pressing against his top teeth, his tongue hard against the roof of his mouth. He’d dialled 999, like the guy had told him, and the voice at the other end of the phone was still asking questions. He could hear the voice rattling away but he was no longer holding the phone to his ear. They had everything they needed to know. He lifted the phone to his ear and said it out loud.

‘Just fucking get here.’

One of the bystanders, a young white woman, turned and glanced over her shoulder at him with a briefly curious expression.

The red helicopter swung into the sky above them, hanging in the air as if swinging on a wire and then descending with a rush of wind. A roar like a movie sound system. Ryan’s chest filled with the vibrations.

The street was filling with people, uniforms, bystanders. Traffic was slowing to watch. A fat white bloke leant out of a car, side window down, and said, ‘Do you know what’s going on?’ Ryan said, ‘I don’t know, mate.’ The fat bloke said, ‘Wannabe gangster. I hope he dies.’ He drove off. There were two paramedic cars now. The street was noisy, and bright too with flashing lights, like a fun fair.

Then the first cop car arrived. A young female officer got out and moved towards Spencer and the paramedics. Luckily she hadn’t thought to look around her. That was what finally got Ryan moving. He didn’t want to leave his friend, but he had to.

3

By the time Sarah arrived, Gallowstree Lane was already closed to traffic and a two-hundred-metre section of the road had been cordoned off with blue and white plastic tape. Portable lights had been brought in, and beyond the tape, the crime scene blazed brightly white against the dark backdrop of the park. Life had been pronounced extinct at the scene and so the body had not been removed. The tent that held the boy was pitched a few yards down from a uniformed officer who stood at the shadowy cordon line, cold and bored, scene log clutched in his gloved hand.

Sarah put her logbook on the dashboard of the car and stepped out onto the pavement.

Gallowstree Lane was a road that took you from east to west, not a main thoroughfare but not residenti

al either. There were AstroTurf pitches at one end, in the middle a lonely shop, and at the end, a scary-looking Victorian pub. There was a vacancy about the place, an absence. Sarah had driven through it many times on the way to somewhere else and it had always given her the creeps. Was it the dimensions – too wide, too open? Was it the sombre, uninviting park with the railings? Someone had told her once that farmers used to drive their sheep into London to sell them here. Sheep markets and hangings: what a day out it must have been. There was another piece of folklore – that the sheep had got anthrax and were buried beneath the park, and that this was what had preserved the road’s undeveloped character, its open spaces. The strange emptiness offered the inevitable opportunities. Gallowstree Lane was both busy with crime – drug dealing and prostitution and fights – and yet also deserted. It was a good place to hurt someone and get away with it.

She opened the boot of her car and split the cellophane wrapper on a white forensic suit. As she began to put it on – legs in the suit, hitching it up, arms in the sleeves, careful not to snag the zip – she watched the specialist search team combing the street, moving in a silent, patient line in their own white suits and blue plastic overshoes, and it seemed to her that perhaps a secular liturgy was occurring. It was a sacrament she held close. In this huge and various city, no murder should go undetected.

Although each detail of the scene was a little different from the last, a bleak familiarity nevertheless washed across the street like an urban watercolour. So many young men dead nowadays that the officers who worked London’s streets knew by heart the established order that followed.

The park would be searched. The prostitutes who worked the road would be spoken to. The CCTV trawl, Sarah noticed, had already begun. The little shop, Yilmaz, metal blinds drawn firmly against the night, had a camera pointing in the direction of the murder, and two officers were knocking on the wooden residential door that was set into the blind side of the shop. A light came on in an upstairs window.

Gallowstree Lane

Gallowstree Lane